- Category: Cinema | Literature | Travel | Culture | Politics

On literature

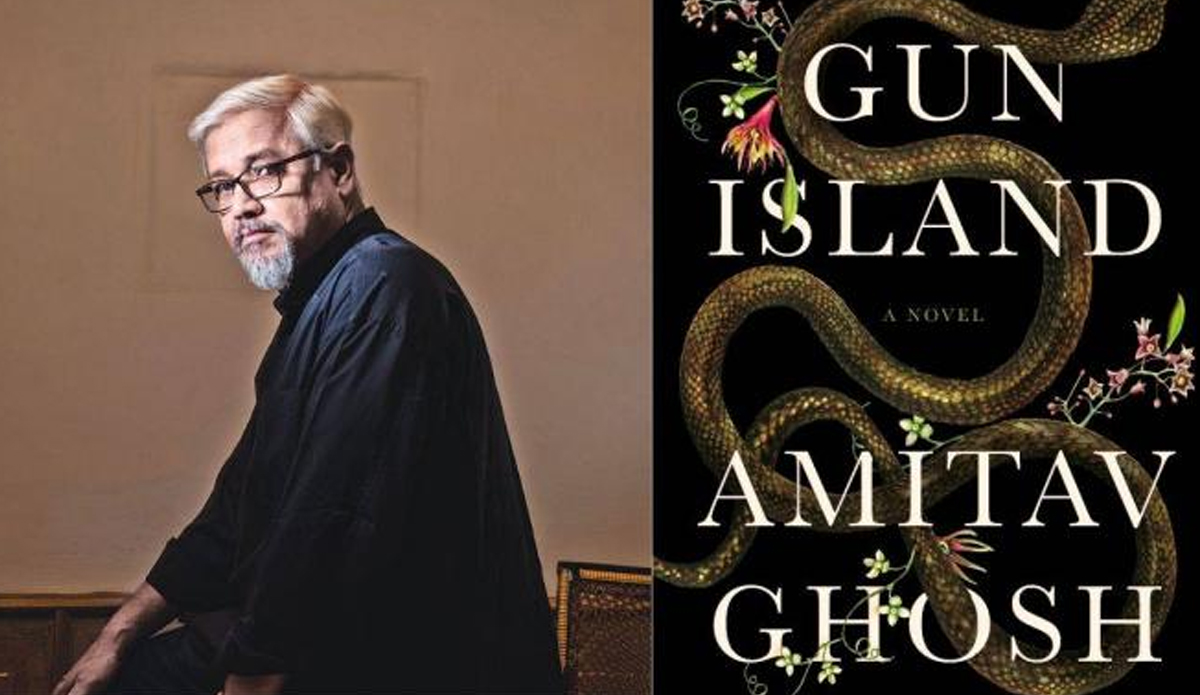

Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island: Anthropology as Literature

M. K. Raghavendra

Amitav Ghosh is trained as an anthropologist but he is best known as a writer of fiction and received the Jnanpith award in 2018, the first writer in English to do so. The relationship between anthropology and fiction is a central one if we are to understand the significance of Ghosh’s work. The medieval university originally had four faculties: theology, medicine, law and philosophy and in the nineteenth century philosophy divided into two disciplines – science and the humanities. The emphasis in science was on empirical research and the testing of hypotheses while that of the humanities was on empathetic insights. Science believed that the humanities could not arrive at the ‘true’, but only at the ‘good’ and the ‘beautiful’.

But the French Revolution of 1789 had initiated changes. The new sense that sovereignty resided in the people made it imperative to study how the ‘people’ arrived at decisions. History, a much older discipline, naturally became part of it but it was also necessary to understand the present through empirical study. The three aspects of the present needing to be studied were the market, the state and civil society. This led separately to the disciplines of economics, political science and sociology. Sociology was initially confined to the five zones that had created historians – France, Great Britain, the United States, Germany and Italy. But since some of these countries were also involved in colonial projects the colonies needed sociology of their own; the study of the civil societies of the colonies thus became anthropology.

Literary fiction and sociology are related in that both study society although in different ways. Social fiction would not have value as literature if it did not have something to tell us about society, but at the same time it must stand apart from sociology. If one were to consider the well-known literary classic Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice the novel sheds light on the various strata in hierarchical society through its characters but the latter are not types merely representing the classes they come from. Where ‘types’ are founded in statistical generalities, individualized characters are based on observed human detail. They strain against the ‘typical’ just as individuals try to transcend class characteristics; the tension between them as individuals and the social classes in which they are located is essential to some literature. This is also true of literature from the former colonies and Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) gives one a clearer illustration of the above proposition. The protagonist’s father in this novel is Unoka, a tribal wastrel who left many debts and is despised by his son. Unoka is adept at playing the flute and when he falls ill to be left in the jungle to die, he takes his flute with him. My argument here is that ‘indebted tribal wastrel’ may be a social type but his attachment to his flute at the moment of his death moves Unoka out of anthropology and into literature.

It would seem that from the 1980s onwards with the large-scale commercialization of education in the US, literature began to be treated differently for pedagogical reasons, and fiction along with film began to be recommended as part of anthropology courses, both to make teaching easier and to bring in more students. Since being prescribed for courses is a key reason why books are purchased we may infer that this made it advantageous for writers of fiction to produce works that might assist in pedagogy. The educated public is itself often led by what universities prescribe for its personal reading since it wishes to continually educate itself; once universities started prescribing literature in social science courses, whatever literature was prescribed became current among the reading public as well. This, it may be conjectured, rendered nebulous the dividing line between the social sciences and literature, and a part of the literary fiction especially from the ‘Third World’ was increasingly read as anthropology.

Amitav Ghosh began as a novelist in the late 1980s and his approach suggests that he writes fiction as anthropology, deliberately illustrating propositions through the characters and events in his novels. He is evidently an avid traveller and also puts in elaborate descriptions of the places he visits as part of his fiction. Anthropology is a large field but there is a discernible overlap between his subjects and one attributes this to the extensive research backing his writing, the unused material each project remainders. His last few books have been: a) set in the Sunderbans (The Hungry Tide, 2004), b) featuring seafaring and migration (The Ibis Trilogy, 2008-15) and c) concerned with environmental issues (The Great Derangement, 2016). In Gun Island he brings all three together, cooking up a novel from the research leftovers of a decade and a half.

Gun Island is written in the first person, the narrator a rare book dealer from Brooklyn named Dinanath Datta, Deen or Dino for short. Dinanath comes to Kolkata annually and he is looking for female companionship. He is knowledgeable about Bengali myths and has researched on one of them associated with the Sundarbans, involving the snake goddess Manasa Devi and a merchant Chand Sadagar, who the goddess tried to make her devotee. Dinanath has only two days left before returning to Brooklyn when he receives a summons from an aged female relative Nilima Bose who runs a trust in the Sundarbans. Nilima has a younger friend Piyali Roy, a marine biologist who teaches in Oregon staying with her and it is the prospect of meeting Piyali that persuades Dinanath to visit Nilima. Piyali is a character we recognise from The Hungry Tide in which she is investigating the Gangetic dolphin and she is still on the subject of dolphins here. But Nilima (also with Piyali’s assistance) is interested in investigating a new legend, that of the ‘Bonduki Sadagar’ or the ‘Gun Merchant’.

The Gun Merchant is evidently Ghosh’s invention and the novel uses it to link the various issues connected to migration in the seventeenth century to Europe, the similar migration today and climate change. Nilima has discovered a shrine to Manasa Devi constructed by the Bonduki Sadagar in the seventeenth century through the legend that the goddess protected the nearby villages from the cyclone of 1970. Needless to add, Dinanath agrees to visit the shrine with Piyali and meets two enterprising young men Tipu and Rafi, the latter saving Dinanath from the horrific king cobra that now occupies the shrine. Tipu unfortunately is bitten but he is saved with some difficulty and becomes increasingly prescient.

Gun Island begins interestingly enough but we wait for Dinanath’s emotional entanglements in vain. What the novel does instead is to feed us elaborate information about the milieu including its myths and its past partly through the dialogue. Ghosh’s tested method in inventing dialogue is to write out long bits of information in a conversational tone and attribute it to a suitable character, put in interruptions like queries, descriptions of the boat or riverscape, details about the dramatis personae and some seemingly striking action (Tipu bitten by the king cobra) not of ultimate importance since it does not affect the plot. The dramatic king cobra is only present briefly and alongside an unspecified number of water creatures like dolphins of various kinds appearing unpredictably to indicate how climate change is influencing animal behaviour, making creatures change their habitats and behave in uncharacteristic ways. Also described are natural occurrences like squalls and unseasonal weather disturbances pointing to climate change. The seventeenth century also had weather changes, apparently, and Amitav Ghosh is making associations. Central, of course, is the story of the Gun Merchant who in trying to evade the fearsome Manasa Devi loses his family and his wealth to typhoons and reptiles and is eventually sold as a slave. This takes the novel to descriptions of the friezes seen in the shrine duly illustrated by drawings in black and white and creating a mystery around them.

The day after he returns from the Sundarbans Dinanath leaves for Brooklyn. He has been disturbed by what he has experienced but interrupts his reverie with a phone conversation with Piyali in Oregon where she describes her roommates experience with bark beetles extending their range unexpectedly, in consonance with the earlier dolphins and reptiles. A friend Cinta (Professoressa Giacinta Schiavon) from Venice and an authority on the city was mentioned earlier and she is due to arrive in Los Angeles to celebrate the acquisition of valuable seventeenth century edition of The Merchant of Venice. Cinta is a historian but open to mythological explanations and points out the similarity between Venetian myths around the tarantula and the mythology involving Manasa Devi and poisonous snakes. The instructive exchanges between Cinta and Dinanath usually take the shape of a one-sided discourse from her punctuated by exclamations of incredulity from his side, concluding in his acquiescence.

In the last part of Gun Island Amitav Ghosh assembles the dramatis personae in Venice including Tipu and Rafi who are immigrants. The book has tried to build up suspense in a manner reminiscent of The Da Vinci Code but what has been held back is too slight – that the Gun Merchant came to Venice in the seventeenth century and the word ‘Bonduk’ has Venetian associations. It would also appear that ‘Gun Island’ is Venice. To see Venice through the Gun Merchant’s eyes Cinta takes Dino on a guided tour of the older sights of the city, her explanations interspersed with Italian exclamations. Here again he is witness to strange happenings like tarantulas seen where they should not be and unexpectedly inclement weather.

Gun Island is not one of Ghosh’s more successful efforts and one even doubts that it fulfils the requirements of fiction. The characters do not stand out and do not enter into relationships with one another. Each one’s entrance into the novel is accompanied by the character’s personal history and we wonder why we are subjected to detail like this when it serves no purpose in plot construction. Mysteries created initially are not resolved except lamely and there are far too many monologues explaining things we are not anxious to know including etymologies of words and terms that we are apt to forget. At the end of the novel full of miracles worked by the occult element in nature we are still left asking questions. Why, for instance, is climate change such a regrettable development today if there had been a similar occurrence in the seventeenth century, and could it also not be temporary?

Amitav Ghosh is a global figure today with a large following and Gun Island is likely to find a huge readership. Still, it is time to question the validity of his tested methods since the novel succeeds neither as anthropology nor fiction. Anthropology is an exciting discipline and discoveries in it can only enrich human knowledge but in Ghosh’s writing we find minor anthropology turned into tepid fiction. If he had been blessed with a speculative imagination Ghosh might perhaps have produced visionary fiction, the anthropological equivalent of HG Wells or the Strugatsky brothers, but that is hardly the case. When he turns research into a mystery novel (which is Gun Island in essence) whatever is revealed at the climax should be highly dramatic at the very least, while all Gun Island offers is the reconstruction of a fictional seventeenth century Bengali merchant’s tale implausibly linked to migration and climate change.

- Category: Cinema | Literature | Travel | Culture | Politics